There was one thing that PIMCO’s investment professionals immediately agreed upon when we gathered – mostly virtually again – for our recent quarterly Cyclical Forum: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the sanctions response, and the gyrations in commodity markets cast an even thicker layer of uncertainty on what already was an uncertain economic and financial market outlook before the onset of this horrific war.

At the outset, we reminded ourselves of the concept of radical or Knightian uncertainty, which has been a recurrent theme in our discussions at PIMCO over the years. In contrast to risk, which can be quantified by assigning probabilities to outcomes based on experience or statistical analysis, uncertainty is essentially unmeasurable and represents the unknowable unknowns. In a radically uncertain environment, detailed point forecasts are therefore not particularly helpful in shaping investment strategy. And so our discussions of the macro outlook remained more high-level than usual, mindful of the wide range of possible scenarios and of the potential for nonlinearities and abrupt regime changes in the economy and financial markets.

Despite the many unknowns, we developed five main conclusions regarding the cyclical six- to 12-month outlook that we think are most relevant for investors at this stage. We will discuss the longer-run, secular ramifications of the current situation at our upcoming Secular Forum in May.

1) An ‘anti-Goldilocks’ economy

First, the global economy and policymakers are confronted with a stagflationary supply shock that is negative for growth and will tend to push up inflation further. There are four main channels of transmission: 1) higher energy and food prices, 2) disrupted supply chains and trade flows, 3) tighter financial conditions, and 4) lower business and consumer confidence due to heightened uncertainty. In combination, these could easily result in what one participant at our forum called an “anti-Goldilocks economy”: an economy that will be both too hot in terms of inflation and too cold in terms of growth.

To be sure, our tentative baseline forecast still calls for above-trend growth in developed market economies overall, though we revised that forecast down by about 1 percentage point to 3% for 2022 from our prewar projections. Growth in general remains supported by the post-pandemic economic reopening and pent-up savings that can support demand.

The outlook for both growth and inflation is clouded by already fragile initial conditions

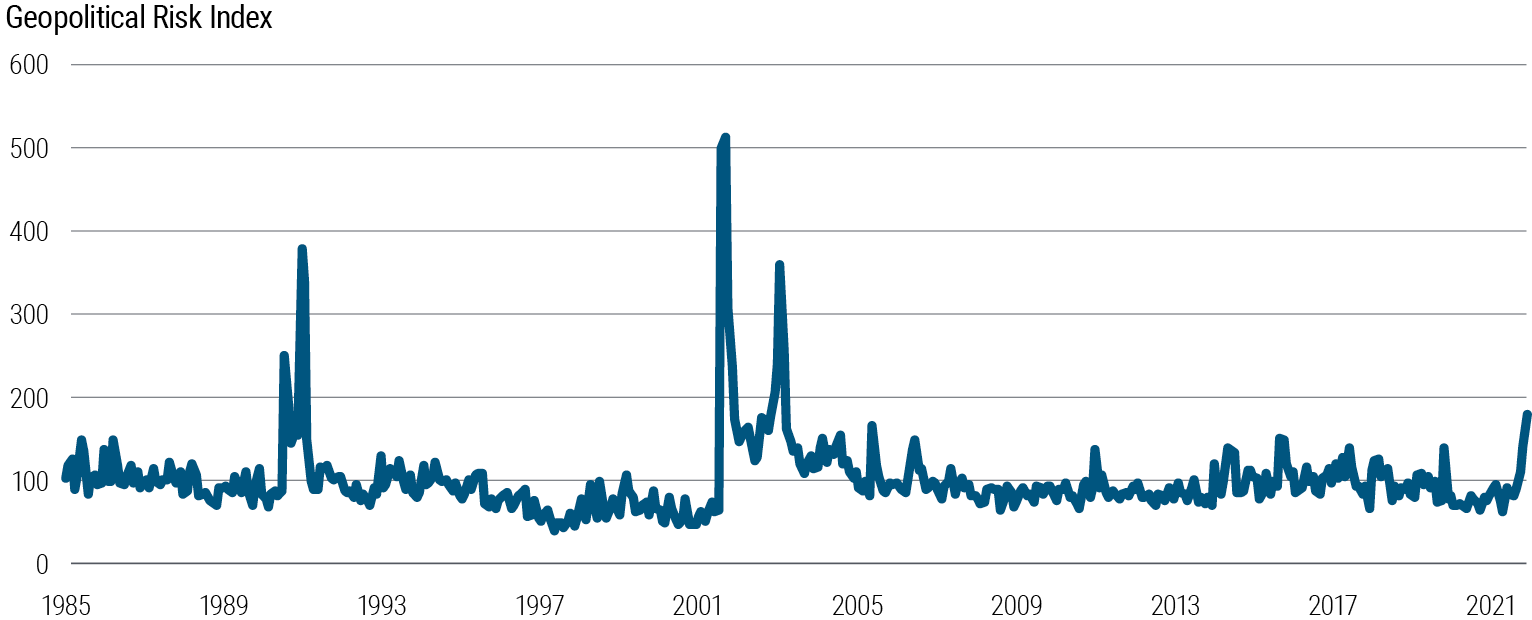

Also, based on the technical assumption that actual commodity prices follow their downward-sloping (as of this writing) futures path, we forecast headline and core inflation peaking at upwardly revised levels in the next few months and then moderating gradually. Note that since the December Forum, we have raised our forecast for average 2022 developed market inflation by 2 percentage points to 5%. However, there are obvious and significant downside risks to this growth baseline and upside risks to the inflation outlook, especially if the war or the sanctions escalate further. We note the uptick in the geopolitical risk index published by researchers at the U.S. Federal Reserve – see Figure 1. Suffice to say, these developments tend to underscore our secular theme of shorter growth and inflation cycles with larger amplitudes.

Figure 1: Geopolitical risk is at its highest level in nearly two decades

2) Nonlinear growth and inflation responses more likely

A second point worth emphasizing is that the outlook for both growth and inflation is clouded by potential nonlinearities related to already fragile initial conditions. In particular, supply chain disruptions were already widespread due to COVID-19, weighing down on output and pushing up costs and prices in many sectors. Russia’s war in Ukraine and the sanction responses have led to further disruptions just as some of the bottlenecks related to COVID had started to ease. While Russia only accounts for 1.5% of global trade, it has a much larger footprint in a range of energy and non-energy commodities. Ukraine is not only a large producer of grain but also an important supplier of parts for Europe’s auto industry and of inputs into chips production, such as neon. Given the complexity of global supply chains, seemingly minor shortages in certain raw materials and components can have an outsized impact on output and prices.

Moreover, the recent COVID-related lockdowns in parts of China have the potential to create new bottlenecks in the global supply chain independent of the evolution of the Russia/Ukraine situation. Even in a scenario where the war ends soon and commodity prices ease, we believe it would be too early to conclude that all is well again. It is also worth keeping in mind that even after a conclusion to the war in Ukraine, the sanctions would likely remain in place for a long time, hampering the flow of trade and capital and exacerbating supply chain issues.

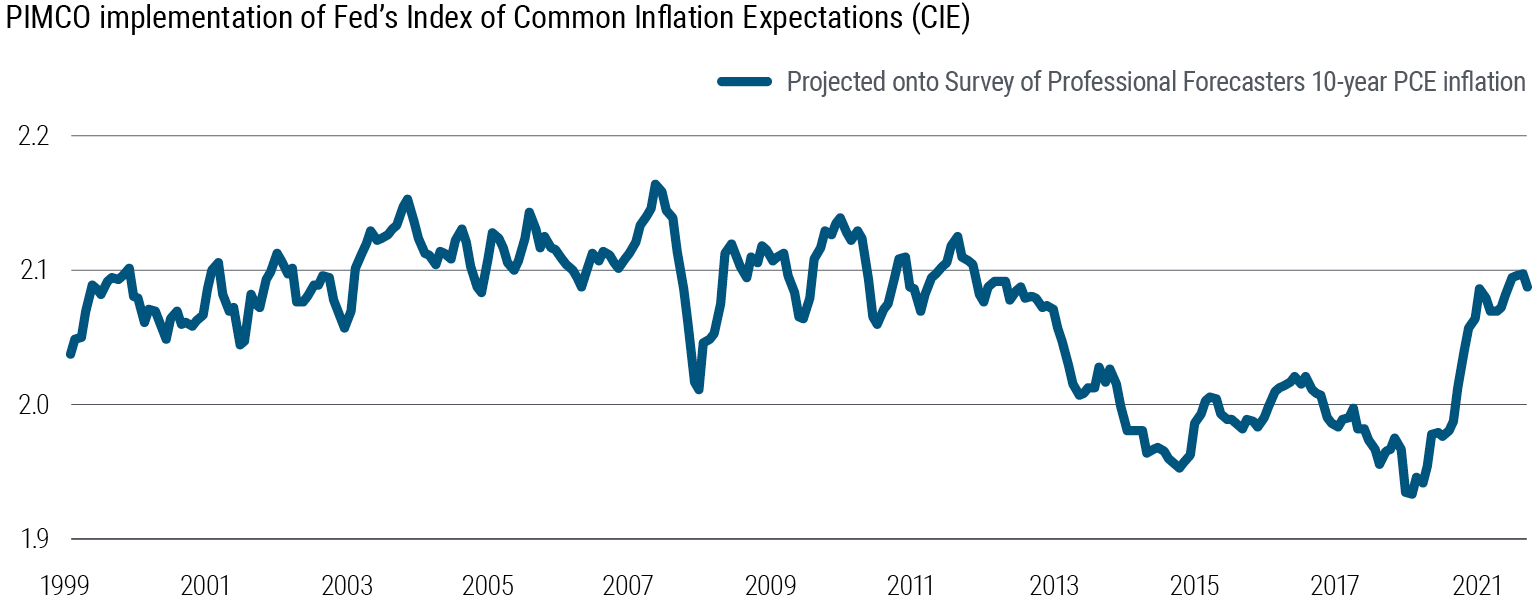

Another potential nonlinearity in the inflation process: Even before the Ukraine shock, inflation was running at multi-decade highs in many countries, and longer-term inflation expectations had been moving higher – see Figure 2 for U.S. data. The additional near-term upside pressure on prices has increased the risk of a de-anchoring of medium- and longer-term inflation expectations and of a wage-price spiral. This is a higher risk in the U.S., where the labor market is already very tight, but given the size of the inflation shock this risk is also significant for Europe. Much depends on the reaction by monetary and fiscal policymakers, which we discuss below.

Figure 2: Measures of U.S. inflation expectations have risen significantly since the pandemic, but currently remain in line with longer-run averages

3) Asymmetric shock begets greater divergence

A third implication of the war in Ukraine is that it will likely lead to a greater dispersion of economic and inflation outcomes among countries and regions over the cyclical horizon. Note that these developments tend to amplify another of our secular themes – a greater divergence of growth and inflation among countries.

Inflation and growth will likely play out very differently across regions

Europe will likely be most affected given its geographical proximity to the conflict; its closer trade, supply chain, and financial linkages with Russia and Ukraine; its great dependence on gas and oil imports from Russia; and the arrival of war refugees. The risk that Europe falls into recession this year and at the same time experiences significantly higher inflation has increased materially, especially if the flow of gas from Russia is disrupted.

China and most other Asian economies have smaller direct trade linkages with Russia but will likely be negatively affected by higher energy prices, declining tourism receipts from Russia, and slower growth in Europe. Moreover, China faces a non-negligible risk of secondary sanctions that could hurt its economy if the conflict escalates further and China decides to align too closely with Russia.

In emerging markets (EM), exporters of commodities like oil, iron ore, copper, metals, wheat, and corn should benefit from more favorable terms of trade. Meanwhile, higher commodity prices will tend to increase already high inflation pressures in most EM economies, especially where inflation expectations are not well anchored. We expect some countries in North Africa and the Middle East will be hit disproportionally hard by rising wheat prices and falling tourism receipts. The economic hardship could also lead to more political instability in the region reminiscent of the so-called Arab Spring more than a decade ago, when sharp increases in food prices were a factor behind political unrest.

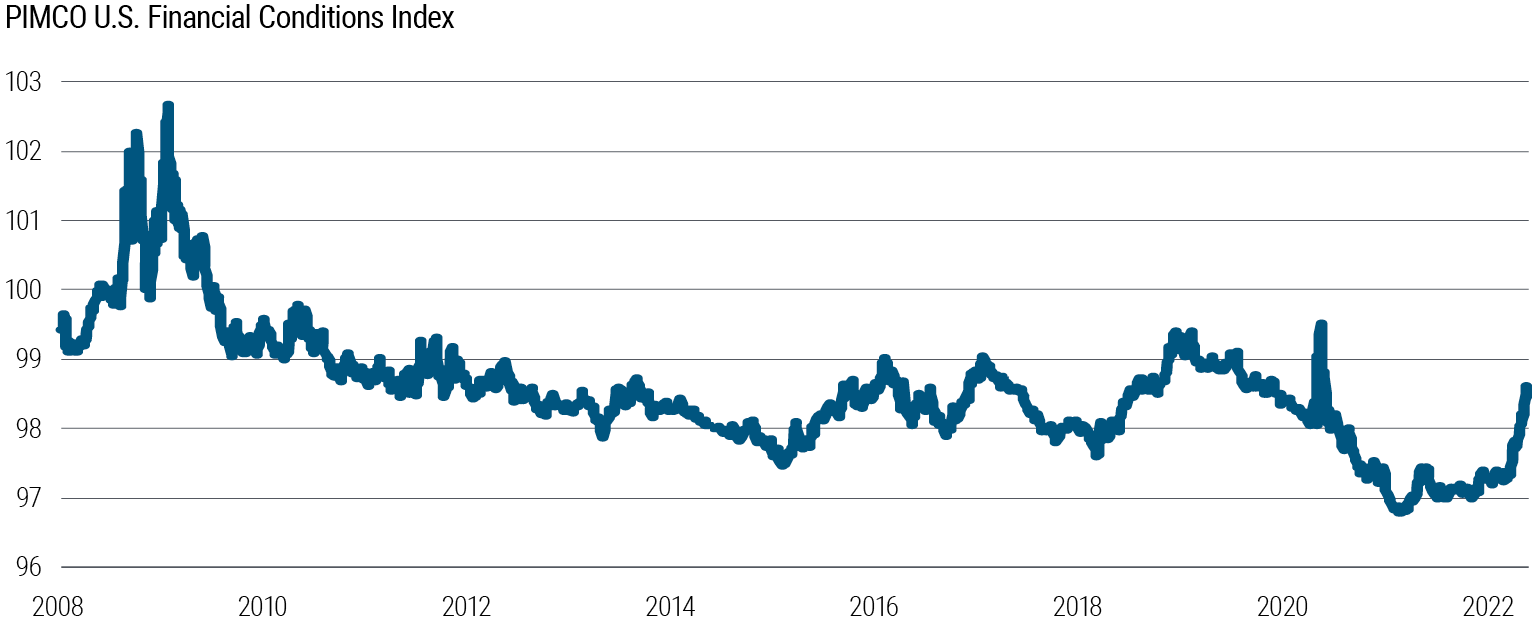

Meanwhile, the U.S. economy appears relatively isolated from the direct effects of the war in Ukraine given minimal direct trade links with the region and its relative energy independence. However, slower growth elsewhere in the world, sharp increases in gasoline prices, potential additional global supply chain disruptions, and a sharp tightening of financial conditions since the onset of the war (see Figure 3) are still likely to dampen growth and push inflation higher this year, in our view.

Figure 3: U.S. financial conditions have tightened rapidly since the invasion of Ukraine

4) Central banks: tug of war

Most central banks seem determined to opt for fighting inflation over supporting growth. In normal times, we would expect central banks to look through the inflationary consequences of a supply-side shock, but these are not normal times, with the current shock coming at a time of already high inflation as the result of the COVID period and ongoing supply chain disruptions. Monetary policymakers therefore appear focused primarily on preventing second-round effects of higher headline inflation and a further rise in already elevated inflation expectations. Needless to say, this also raises the risk of a hard landing further down the road and implies a rising risk of recession later this year or in 2023; this is not our baseline, but a risk to monitor.

The European Central Bank (ECB), the central bank that is closest to the Russia shock in terms of the GDP risks and has – together with Japan – the weakest underlying inflation dynamics, demonstrated at its March meeting that it does not intend to be knocked off its course of removing accommodation given the current outlook.

The U.S. Federal Reserve at its March meeting started a new tightening cycle by lifting the fed funds rate off the zero bound and signaled a series of rate hikes through this year combined with a runoff in the balance sheet likely to start in one of the next two meetings. (Read our blog post on implications from the March Fed meeting.)

The Bank of England raised rates for the third time in three months in March and signaled that it will probably tighten further. Many other central banks in both developed and emerging markets are on a tightening path given rampant inflation pressures. The one major exception is China, where below-target inflation, a strong currency, and concerns about growth have led to moderate monetary easing in recent months and make any tightening moves this year look unlikely.

Most central banks are opting to fight inflation over supporting growth

Thus, for the first time since the stagflationary 1970s and early 1980s, the major Western central banks led by the Fed are unlikely to ride to the rescue in the face of a negative growth shock given that it is accompanied by a positive shock to inflation. This increases the risk of weaker growth or even a recession in the developed economies and damage to financial markets.

As we stressed in our Secular Outlook, “Age of Transformation,” our baseline remains for low neutral real policy rates owing in part to persistent long-term drivers and in part to financial market sensitivity to higher rates. But higher inflation is likely to lead to difficult choices for central banks – and opportunities for active investors if ongoing central bank tightening does lead to financial market breakages.

5) Fiscal policy: muted response

Governments reacted to the pandemic with every tool at their disposal, supported by monetary policy. Yet with deficits and debt now significantly higher and central banks ending quantitative easing and raising rates, the fiscal response to the current shock is likely to be much more muted.

We firmly believe more fiscal easing is coming in Europe, partly in the form of higher defense spending (which would take time to become effective) and partly through transfers and tax subsidies aimed at cushioning the impact of higher energy costs on disposable incomes. However, these measures would likely only partially offset the automatic drag from the expiration of temporary support measures implemented during the pandemic. Also, further steps toward a shared fiscal capacity via the EU budget, this time for defense and more renewable energy investments, seem likely. However, it could be a slow process that will have an economic impact only well beyond our cyclical horizon.

In the U.S., only at best minor additional fiscal support looks likely in the near term given the political near-stalemate in Congress. And after the midterm elections in November, assuming a Republican majority in the House and possibly also in the Senate, gridlock may prevent any further fiscal easing for years to come. While this is not great news for cyclical growth, it should be helpful in moderating inflation pressures because, as the pandemic episode served to illustrate, inflation is not only a monetary but also a fiscal phenomenon – it takes two to tango.