Secular theme: The aftershock economy

Ongoing disruption – to the global economic and financial order, to the geopolitical balance, and to the scale and scope of government policy interventions – has defined the first three years of this decade and will, we believe, remain a new reality that investors need to recognize over the next five years. This has been a trend we’ve noted in recent PIMCO Secular Outlooks and one we revisited at our latest annual Secular Forum in May.

Our Secular thesis last year, “Reaching for Resilience,” argued that in a more fractured world, governments and businesses would increasingly prioritize safety over short-term economic efficiency. We flagged potential inflationary pressures as companies friend-shore supply chains and as governments boost spending on energy initiatives and national defense.

While that thesis broadly continues to hold, our outlook for the next five years must incorporate and assess a number of major developments since our May 2022 forum, including

- Hawkish monetary policy pivots in response to the largest sustained surge in global inflation in 40 years

- A debate over the destination for neutral monetary policy rates once (or if) central banks return inflation to target levels

- Three of the largest bank failures in U.S. history and the collapse of Credit Suisse in Europe

- The passage of an ambitious U.S. fiscal trifecta – the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the CHIPS and Science Act – in support of a newly assertive American industrial policy push, which will serve as a cyclical and secular tailwind as funds are released into the economy

- Conflicting signals on the economic and geopolitical direction of China amid President Xi Jinping’s “third act”

Our secular views also build upon our latest Cyclical Outlook, “Fractured Markets, Strong Bonds,” which anticipated modest recessions across developed markets, with tighter credit conditions raising downside risks. We said major central banks are near the end of their rate-hiking cycles, although not yet close to normalizing or easing policy, while future fiscal responses may be constrained due to high debt levels and the role of post-pandemic stimulus in fueling inflation.

In this environment of ongoing and multiple disruptions, short-term cyclical dynamics are having more long-lasting secular consequences, ushering in what we’re calling “the aftershock economy.” Here we share some key economic and investment implications we took away from our 2023 Secular Forum.

Macroeconomic volatility and geopolitical tension likely to persist

It’s worth remembering how unusual the first three years of this decade have been in comparison with the 2010s.

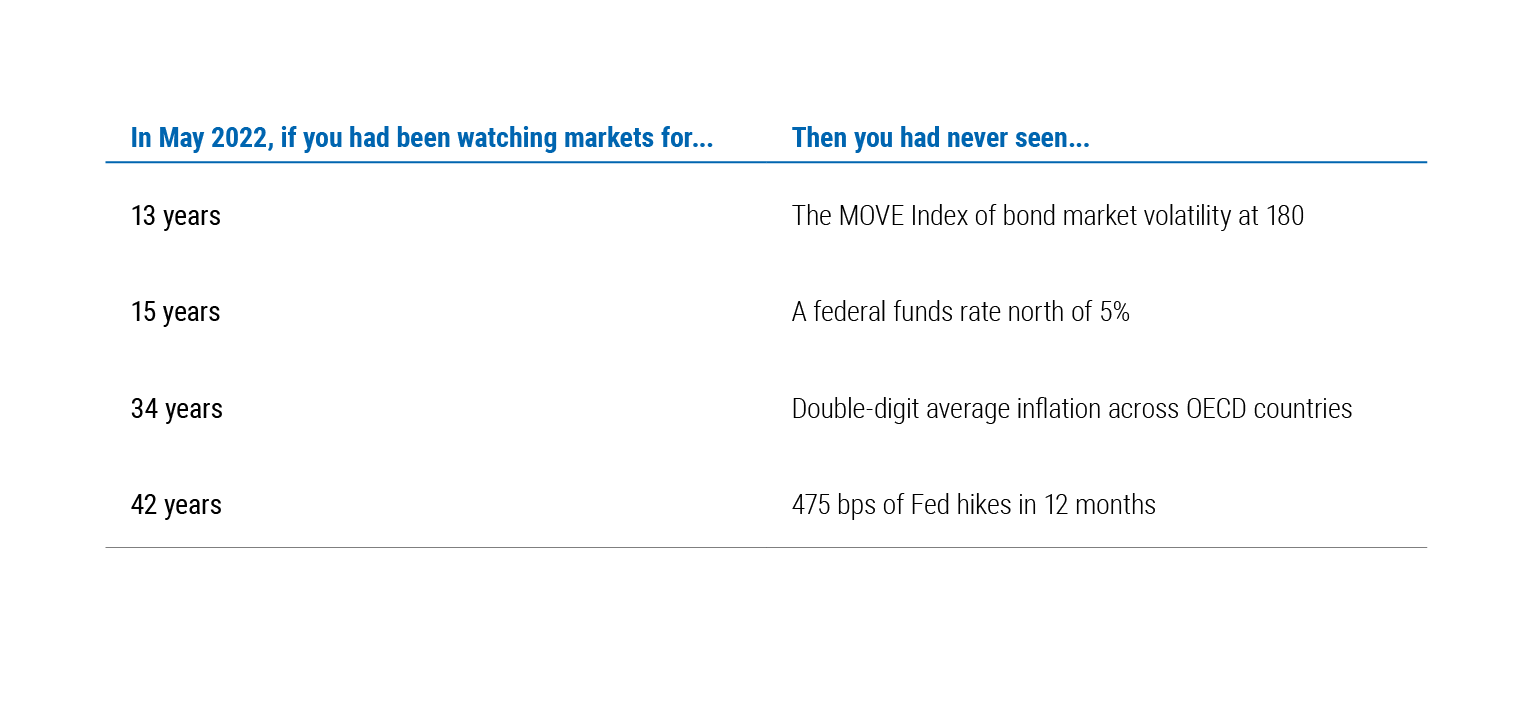

The world faced a once-in-a-century pandemic, which authorities countered by locking and shutting down big chunks of the global economy and providing massive monetary and fiscal stimulus. In time, that stimulus, along with the cost of reopening the global economy and restoring supply chains, fueled the sharpest sustained surge in global inflation in 40 years. Central banks eventually responded with the most aggressive global rate-hike cycle in decades, with consequences that included a financial market rout in 2022, a banking crisis, tighter credit conditions, and widespread forecasts of a recession this year or next (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: As of last year’s Secular Forum (May 2022), several things we hadn’t seen in a long time

These events will likely reverberate for years to come. We expect more frequent and more volatile business cycles, with less scope for governments to deploy countercyclical fiscal policy, and with central banks less willing to double down on administering unlimited doses of quantitative easing (QE).

We anticipate an era in which constraints on supply – not just shortfalls of demand – as well as enduring post-pandemic labor market shifts become significant sources of economic fluctuations, and continue to put upward pressure on global price levels.

While we broadly share the prevailing view that global growth on average over our secular horizon will disappoint compared with the pre-pandemic experience, we also believe that the risks to growth are skewed decidedly to the downside. The reasons include the risk of sharper and more persistent tightening of global financial conditions due to recent banking system turbulence and the policy response to it, sharper contractionary effects from synchronous central bank rate hikes, possible escalation of war in Ukraine, a potential faltering of China’s economic recovery, and rising risk of a U.S.–China confrontation over Taiwan.

Our forum included presentations on the potential trajectories for real and nominal neutral interest rates and the destination for central bank inflation targets over the next five years. We believe that neutral long-run real policy rates in advanced economies will remain anchored over the secular horizon in the New Neutral range of 0% to 1% by powerful long-term forces of aging demographics and sluggish productivity growth.

The U.S.–China relationship is expected to continue to dominate geopolitical dynamics, and we may have already entered “Cold War II,” as historian Niall Ferguson – one of the forum guest speakers – suggested, with implications for countries worldwide as alliances and trade relationships realign. That said, we expect that trends in global trade and investment patterns will be driven much more by “de-risking” than they are by “decoupling.” Supply chains are not being fundamentally decoupled; they are for the most part in the process of being globally recoupled in the direction of “friend-shoring,” a trend that at least in the U.S. is already underway.

Policymakers face constraints and fatigue

Notwithstanding the post-pandemic surge in global inflation, we believe central banks will do what it takes to keep longer-term inflation expectations anchored at their existing inflation targets. We don’t expect developed market central banks to formally change their targets, but do expect those targeting 2% to be willing to tolerate “2-point-something” inflation as part of an “opportunistic disinflation” strategy, in which they expect a shortfall in aggregate demand during a future recession to return inflation to target from above. Relative to our baseline, we think that the risks to inflation are skewed to the upside.

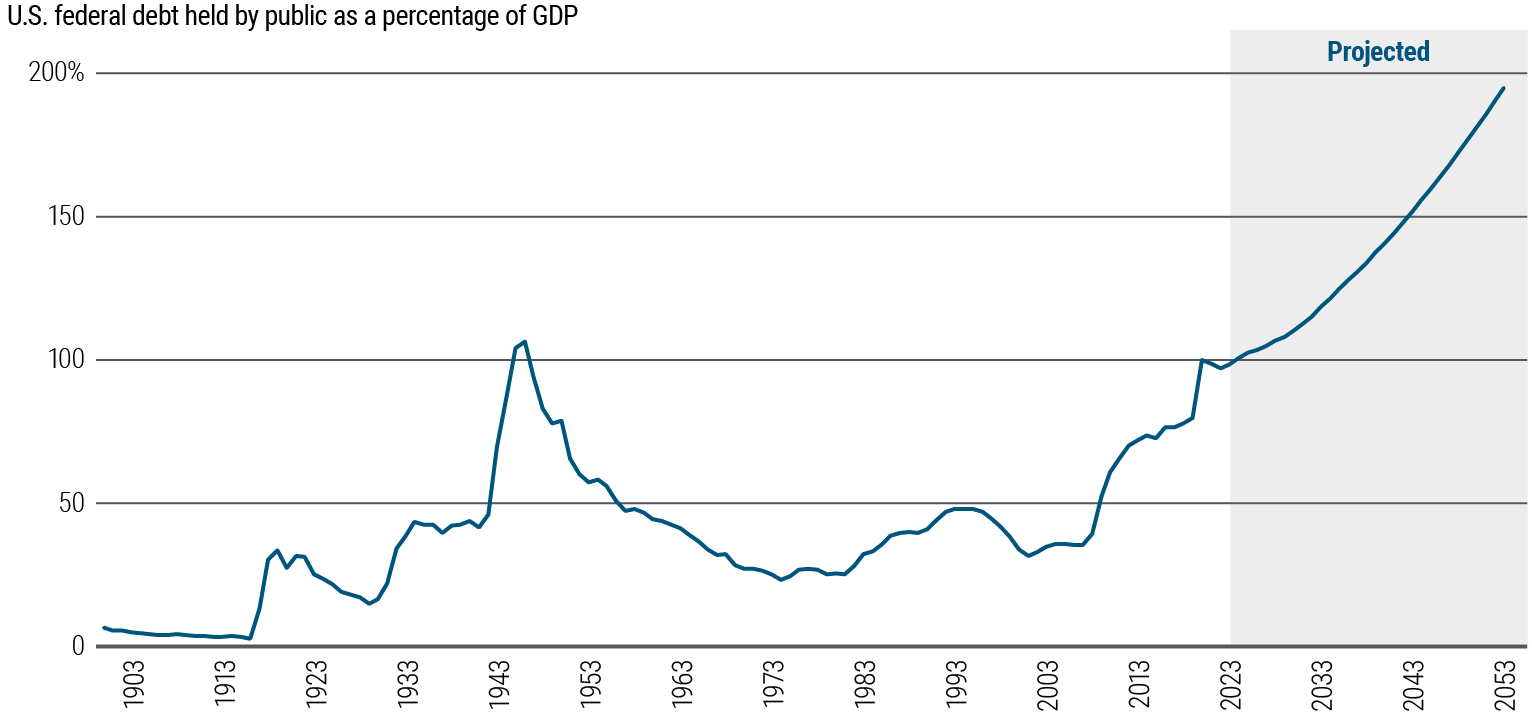

Turning to the policy toolkit, we believe over the next five years that, given the current astronomical levels of sovereign debt relative to GDP (see Figure 2), fiscal space will be more limited than in the past – either by politics or financial markets – and will constrain the ability of fiscal policy to soften future economic downturns.

Figure 2: Ratio of U.S. debt to GDP projected to rise substantially over the long term

We also anticipate the possibility that global central bankers will begin to suffer from “QE fatigue.” For the first time in decades, elevated and stubborn inflation is highlighting the fact that, as with any economic decision, QE and fiscal largesse can have costs as well as benefits.

This may have ramifications for future policy, as playbooks that worked over the past 15 years may become less relevant. And in a world of QE fatigue and constrained fiscal capabilities, a cyclical disruption could become more secular.

With less scope to deploy traditional fiscal policy, governments may turn over time more to regulatory interventions. That will create winners and losers across affected sectors, while presenting opportunities for active asset managers.

In light of the collapse of Credit Suisse, as well as the failures and the cumbersome resolutions of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank, we believe that renewed calls to rethink and redesign the financial architecture within which banks operate will finally gain traction.

This will imply, at least in the U.S., tighter regulation that requires banks to have more capital and hold more liquidity. Banks’ liquidity-intermediation capacity will likely shrink further, and some traditional activities will likely go into private markets and nonbank lending. We see a window to step in as a senior lender in areas once occupied by regional banks, such as consumer lending, mortgage credit, and various forms of asset-based finance.

Potential disruptions and aftershocks abound

Our forum discussions informed our broad baseline outlook described above, but they also highlighted the remarkable array of aftershocks that could emerge over our secular horizon.

Outcomes of the 2024 elections for the White House and control of Congress could have significant implications for U.S. fiscal and monetary policy, as well as foreign policy. The political tenor means that there will likely be even more pressure to be “tough on China,” regardless of who is in the White House in 2025.

Similarly, the January 2024 presidential election in Taiwan could prove pivotal for U.S.–China relations, as those nations shift toward a structural rivalry and as China increasingly asserts itself across Asia. If the Kuomintang (KMT) defeats the more pro-independence incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), it may decrease the secular risk of confrontation over Taiwan.

Even absent a deepening military conflict, there is potential for a significant escalation of the U.S.–China rivalry on other fronts. The economic implications could include demand surges and supply shocks; further shifts in the global trade landscape amid nearshoring, friend-shoring, and duplication of supply chains; and even China potentially reconsidering its holdings of U.S. Treasury bonds. Meanwhile, an anticipated U.S. executive order on capital outflows is likely a beginning, not an end, over the secular period of a ratcheting up of restrictions on capital flows in addition to what has already been seen on export controls.

There are risks around the outlook for inflation, both in the U.S. and globally. While not our base case, there is the possibility that U.S. inflation remains stickier than anticipated and does not drop below 4% in the intermediate term, or remains closer to 3% over our secular horizon.

There are uncertainties about how responses to inflationary pressures will play out across emerging markets (EM) versus developed markets (DM). There is also uncertainty about the longer-term effects of high realized inflation on inflation expectations, given the persistent rise in inflation to levels previously not experienced in decades.

Central banks could continue to confront the challenges of balancing the conflicting policy objectives of maintaining growth, reducing inflation, and minimizing financial instability, while demonstrating that they’ve learned policy lessons from the “roaring inflation” 2020s. The potential for widespread adoption of central bank digital currencies (CBDC) or privately provided stablecoins also looms as a possible disruptor for the global financial order and – although not likely over our secular horizon – a possible challenge to the dominant global status of the U.S. dollar.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Europe in particular has faced shocks to energy supply and demand that made energy security and independence paramount objectives. That may force certain countries to further invest in energy sources and hasten the green transition, potentially contributing to inflationary pressures.

The wide adoption of large language models of AI is a legitimate “wild card.”

The accelerated adoption of large language models (LLM) of artificial intelligence (AI) is a legitimate “wild-card” factor. Over our secular horizon, it could have a material positive influence on productivity growth, which could put downward pressure on inflation and upward pressure on real interest rates. That influence could be seen in areas such as autonomous driving, reduced switching costs for consumers, and improved information flow. AI could also increase human longevity, for example by speeding medical breakthroughs such as immunotherapy cancer treatment using nanotechnology.

There are also significant risks associated with the recent swift advances in AI, including increased spread of disinformation via social media and risk of cyberattacks. Moreover, AI has the potential, even over our secular horizon, to worsen trends in income inequality and contribute to further political polarization and populism.